Then and now, under foot or in my mind, always a special place.

My memory places, the places I recall with affection and pride, range from my boyhood home in Valley City, North Dakota, to the Grand Forks hospital room where I watched my little grandson hold his just-born baby sister. Prompted to sing to her, he sang a bit of “Puff the Magic Dragon.”

I remember standing at my grandmother’s grave in southwestern Norway, telling her about the son who left for America at 18 and never was able to return. She knew she likely would never see him again, a cousin told me. For three days before my father left, she moved her cot next to his.

The places in my heart include a favorite camping spot among the pines in northern Minnesota, a rise overlooking the Missouri River in western North Dakota where I can imagine Lewis and Clark passing by, and a field in West Africa where I visited a Peace Corps-serving friend, also a UND graduate, and helped her plant trees to hold back the Sahara Desert.

Those places, and my University.

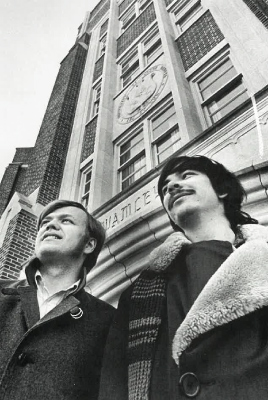

Merrifield Hall, fall 1971

Tau Kappa Epsilon

I remember as if it was yesterday that first day I set foot on campus as a student, 56 years ago. I had been there twice before, once as a high school senior and once as a junior high student tagging along with my big brother Jerry, who introduced me to his fraternity brothers at Tau Kappa Epsilon (the building stands, but with new Greek letters out front). It was a Sunday morning, and a few of the lads sat in the living room, talking and drinking coffee and reading the Sunday papers. (I want to say the Kingston Trio sang from a stereo that morning, but I may be imagining more than remembering that.) It seemed a time of important transition. It seemed so adult, so inviting, so promising.

Then in September 1967, I walked across campus, a freshman wearing a new sweater, trying to look collegiate as I shuffled through leaves fallen from old oaks, elms and maples. I remember it was sunny and warm and there were so many of us, and I wondered: Was I worthy? Did I belong?

Memorial Union, circa 1967

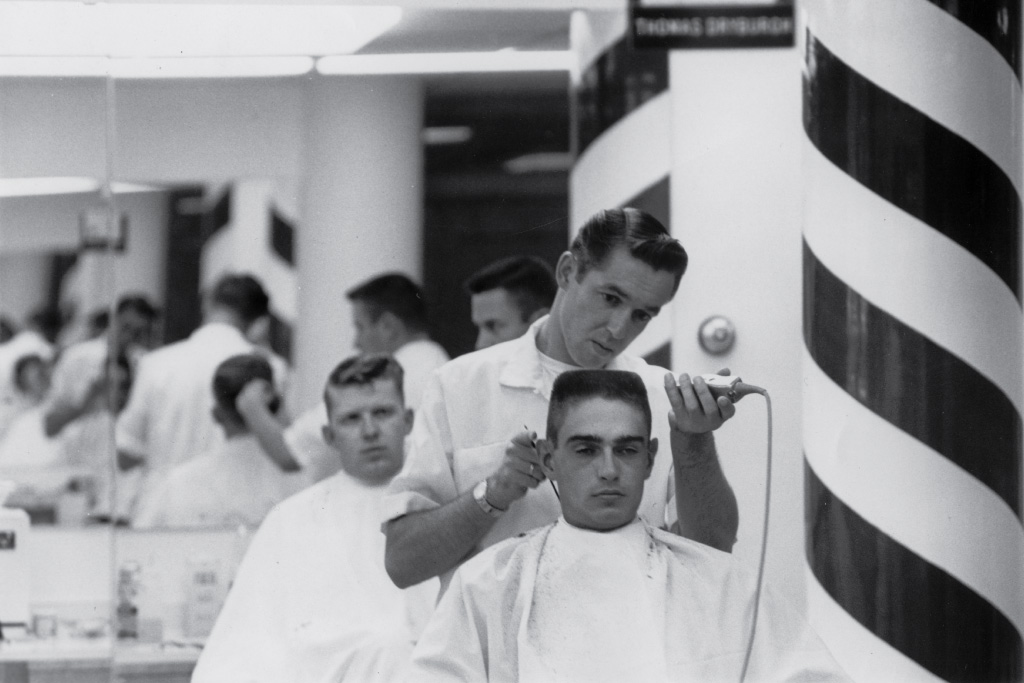

Memorial Union Barber Shop, 1970

Of the places of my life, places that shaped me and earned my affection, my University stands out. The word itself brings to mind something solid and enduring, changing but preserving, too, a place of honor and tradition but also a place of experiment, surprise and discovery, where questioning is encouraged and dissent is tolerated.

So much has changed on campus since I first arrived in the fall of 1967, excited and scared, wondering whether I had the stuff to succeed here. Especially in the past couple of years, with construction of the new Memorial Union and other major projects, the face of this venerable place has changed considerably.

Some of my memory places are gone. The new Union is bright and airy, and students seem to have embraced it as a good place to meet and mingle and just be, but I still think wistfully of the old place where we gathered, played cards, ate lunch, flirted, argued about war and movies. I miss Tom and Jerry, the amiable barbers who held court in their basement shop. I remember the restless nights of speeches and protests that filled the old Union following the killing of four students at Kent State in May 1970.

It’s difficult now, with all the development, to place precisely the line of anti-war protesters, students and faculty, that stretched from the Union to the Law School in the late ’60s. Gone, too, is the little Valley Dairy convenience store off Cambridge, and Budge Hall, where I had an office as a graduate teaching assistant in history in the late 1970s. In that stuffy old building of burnished wood and creaky stairs, I felt a kinship with generations of young scholars.

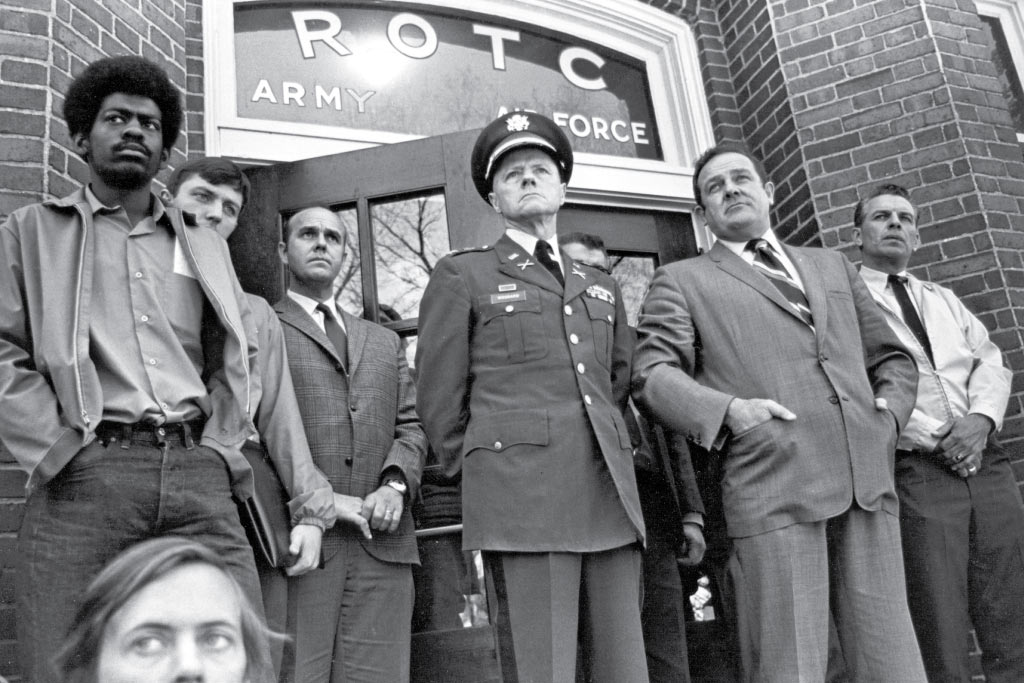

Tom Clifford (second from right) following shootings at Kent State, May 1970

Kent State protest, 1970

History. The word instantly conjures images of Merrifield Hall, the long, muted hallways and bare classrooms and my professors – men and women who were the university to me: pipe-smoking P. V. Thorson and “Poppa” Robert Wilkins in History, the courtly Bob Lewis and drawlin’ John Little in English, dear Graciela Wilborn and gentle Modesto del Busto in the Spanish wing of Modern and Classical Languages.

Work crews are busy now updating Merrifield, giving it a more open face onto the Quad and making it more accessible, more technologically current, and we who know and love the building watch nervously. With three old friends, all of us fans and self-appointed guardians of Merrifield, I wandered through the nearly century-old Collegiate Gothic structure once more last year before the renovations began. We wanted to see the gargoyles and alcoves where we might have sat between classes, napping or reading.

“We wander the halls,” I wrote about that unguided tour, “and remember the sounds of panic and purpose, the smells of bookbags and office coffee and wet wool hung in hallways or draped over radiators in winter. We remember the learned scholars who strode from office to classroom and talked – talked to us – of Robespierre and Hemingway and Aristotle.”

I sat again in Room 217 and remembered Gordon Iseminger describing the fog that lifted just in time for the French to prevail at Austerlitz, and I felt my hand cramp at the memory of the blue books I filled to show what I knew, what I had learned. The liberal arts are at the heart of a university education, and Merrifield Hall is where the liberal arts are practiced and respected.

It is still a smorgasbord of ideas and experiences, I tell students now. Seize the day.

If I could do those years over, I think I would branch out more, go deeper and experience my University more broadly. I would master Spanish and tackle algebra. I would go to more plays and spend more time in the art museum, maybe a little less at Frenchy’s or Judy’s.

In a special Fall 1970 orientation issue of the Dakota Student, where I was editor, we ran a double page spread of images from the previous year, with a short copy block, I believe written by me: “In the course of just one academic year we can listen to gifted speakers of national reputation, quiz politicians on contemporary issues, experience one of the world’s greatest jazz trios, observe high quality dramatic presentations. … We can sing the lead in a musical, draw a cover for Tyro, lead a panel discussion on the war. …”

It is still a smorgasbord of ideas and experiences, I tell students now. Seize the day.

Chuck Haga and Mike Jacobs, editor and managing editor of the Dakota Student, 1970

Beyond the campus, Frenchy’s is gone, but Judy’s endures, as does the Red Pepper. On campus, Squires, Walsh and a few other dorms are memories, as are the former homes that housed the Women’s Center and the Era Bell Thompson Center, their important roles incorporated elsewhere. A few of the old Greek units are history, too, but the Sigma Chis still hold Derby Days, the ATOs have a new house, and every time I pass by the Alpha Phi house I remember the day in the early 1980s when the sisters “captured” me, a newspaper columnist and presumably a low-level local “celebrity,” and held me for ransom. I had to call friends and get them to pledge money for the sorority’s fundraiser.

George Starcher and Tom Clifford

I have known more than a half-dozen UND presidents. I like the new guy, who is personable and listens and cares about the right stuff, but George Starcher and Tom Clifford – though markedly different men – remain to me models of a university president.

Clifford was friendly, accessible and a master at dealing with the various publics who had an interest in the university. The stories of him reaching into his own pocket to rescue a student who couldn’t make rent or meet some other crisis or they’d have to leave school – those stories are many and true. I remember Clifford best, though, from the day in May 1970 when he stood in the doorway of the ROTC building, where hundreds of us had gathered, angry about the killing of students at Kent State. He knew we were sad and angry, and by showing that, he helped to defuse a situation that could have turned ugly.

Starcher was more formal, a mathematician who carried himself with old school dignity. He believed in the vital importance of academic freedom, and he defended our right as students to hear and express controversial views. I can hear him in this quote my friends at the Alumni Association found:

“The University is not the campus, not the buildings on the campus, not the faculties, not the students of any one time – not one of these or all of them. The University consists of all who come into and go forth from her halls, who are touched by her influence and who carry on her spirit. Wherever you go, the University goes with you. Wherever you are at work, there is the University at work.”

And there is my University, a place of mind and grounds, of promise and memory. \\\

Chuck Haga had a long newspaper career with the Grand Forks Herald and the Minneapolis Star Tribune. Though he retired as a full-time journalist in 2013, he continues to write regular columns for the Herald, and serves as an adjunct professor in UND’s Department of Communication and is serving on the committee to celebrate the journalism/communication department’s 100th anniversary. This semester, he’s teaching Comm 200 to 25 young minds.