As UND alum Bill Alkofer’s 40-year photography career is shuttered by ALS, he turns his attention to his ‘bucket list.’

In the glowing red light of the newspaper’s darkroom, Bill Alkofer, ’85, presses play

on the

battered tape deck and punk rock blasts forth.

Three-chord angst gets us through another Dakota Student deadline, achieved yet again as the sun rises.

Materializing out of that windowless room is a cavalcade of photographs, sharp visuals to focus our written words, to document early-1980s campus life. We are learning to be journalists, and, with Nikon in hand, Bill has found his calling.

The staff of the Dakota Student in 1982, from left, back row, Artist Tom Kee, Entertainment Editor Bill Thorness, Managing Editor Nancy Krier, Editor Mike Burbach, stand-in for Sports Editor Barry Obenchain; front row, Chief Photographer Greg Booth, Associate Editor Laura Sands, and Photographer Bill Alkofer. Missing: Bob Stjern, Associate Editor.

Bill and I are on the top deck over the St. Paul Saints outfield as their lead slips away. From the borrowed wheelchair, he’s telling me how he used to photograph the game.

“This was before GoPro. I had put a camera in first base, and I’d put one pointing straight up in home plate. Also one on the umpire’s helmet.” The Saints loved it. They asked him to throw out the first pitch and introduced him as the Inventor of the Umpire Cam. “I went into the bullpen and practiced,” says the tall photographer. “Threw a strike.”

Bill’s recently back in St. Paul, much nearer to family and friends than he was in Long Beach, California, his last assignment as a photojournalist, shooting freelance for the Orange County Register. He needs help now, more every day, and at the ripe old age of 59 he’s done taking pictures. ALS — Lou Gehrig’s Disease — has robbed him of mobility, stability, and the use of nine of his 10 fingers. Without his raison d’etre, Bill is driven to “enjoy every sandwich” and tell one last story.

Warren Zevon’s famous phrase resonates, but Bill’s own maxim is shutter-speed focused: Pay Attention.

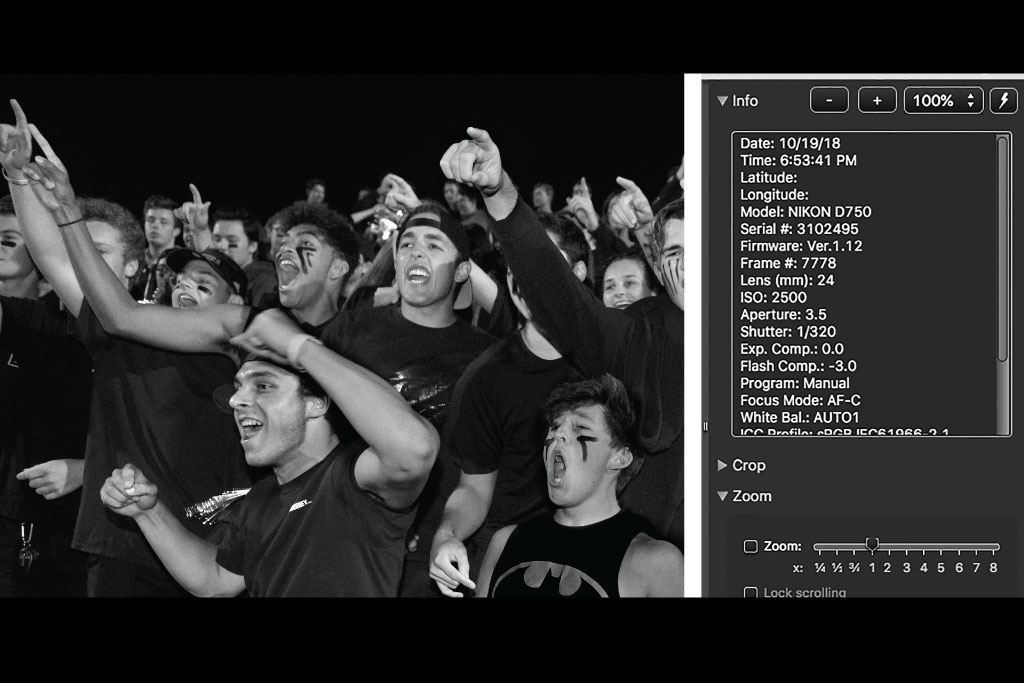

For instance, his divergence into ALS “started on October 19, 6:53 and 41 seconds, 2018,” he says. “I know the exact moment when I noticed the onset. I was shooting a football game and was going to hold the camera over my head and I couldn’t do it.”

Sports is Bill’s arena, discovered gloriously at UND. “I love hockey,” he says. “My spot for my shot was four steps up from the opposing team’s bench.

That’s where the Grand Forks Herald photographer Dean Hanson shot from. I would watch what he did, and I’d shoot what he did.”

He continues the technique as he builds the career. “On my days off, I’d hang out with the newspaper’s best baseball photographer. I’d just stand next to him and he’d tell me, ‘OK, he’s going to steal the base.’”

But I don’t let the deflection fool me, because I’ve seen his work, spanning four decades.

In big-city papers like the St. Paul Pioneer Press and the Register. From gigs at the Olympics, twice, Lillehammer and Nagano. Normandy for the 50th anniversary of D-Day. So much more. Yeah, pay attention, but take that inspiration and layer on a unique perspective.

It begins at UND, where Journalism professor Zena Beth McGlashan schools a sleep-deprived Bill about freedom of the press, Harley Straus does independent studies with an unusual student, and department chair Vern Keel has his back.

Each weekend, his eye roams the UND hockey arena, looking for the goon. “I don’t like Guy Shooting the Puck,” he says. “I like more Guy Getting an Elbow in the Face.” Later, photographing a big fight at a pro game from behind the penalty boxes, he overhears the old goon telling the new goon that he should lead with his left, because the refs might not notice.

“Look at the action away from the ball or the puck, that’s where the real game takes place,” he says.

Today you can stroll the Ralph Engelstad Arena and see Bill’s perspective, plastered large across its walls.

Terance “Turbo” Frasier of the Saint Paul Saints dives back to first base and right into the lens of Bill’s hidden base camera.

Fans at a J. Serra High School football game in San Juan Capistrano cheering their team. This photo was taken at the exact moment when Bill first experienced the onset of ALS symptoms.

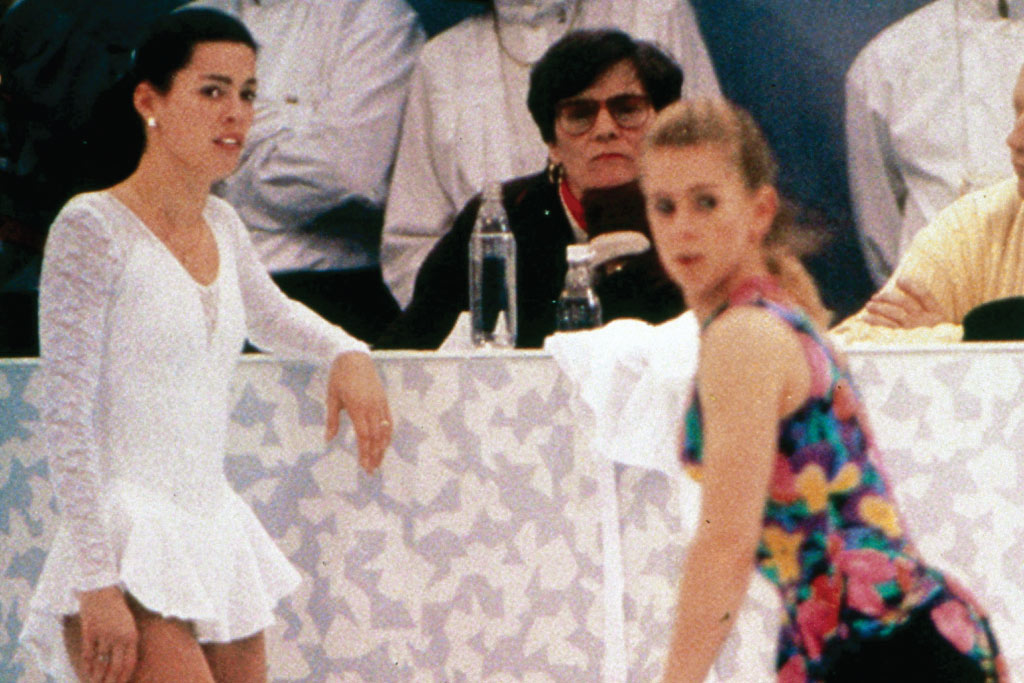

Nancy Kerrigan glares at Tonya Harding as the figure skaters share the ice in a practice session at the 1994 Winter Olympics.

A fight between players from the Anaheim Ducks and the Arizona Coyotes.

On a story in Los Angeles, I look up Bill for shenanigans.

We stroll through Disneyland, and I comment on the rides I missed as a kid. Soon we are two oversized galoots in a Mad Tea Party cup, and somehow Bill has procured a pink baby bonnet to wear.

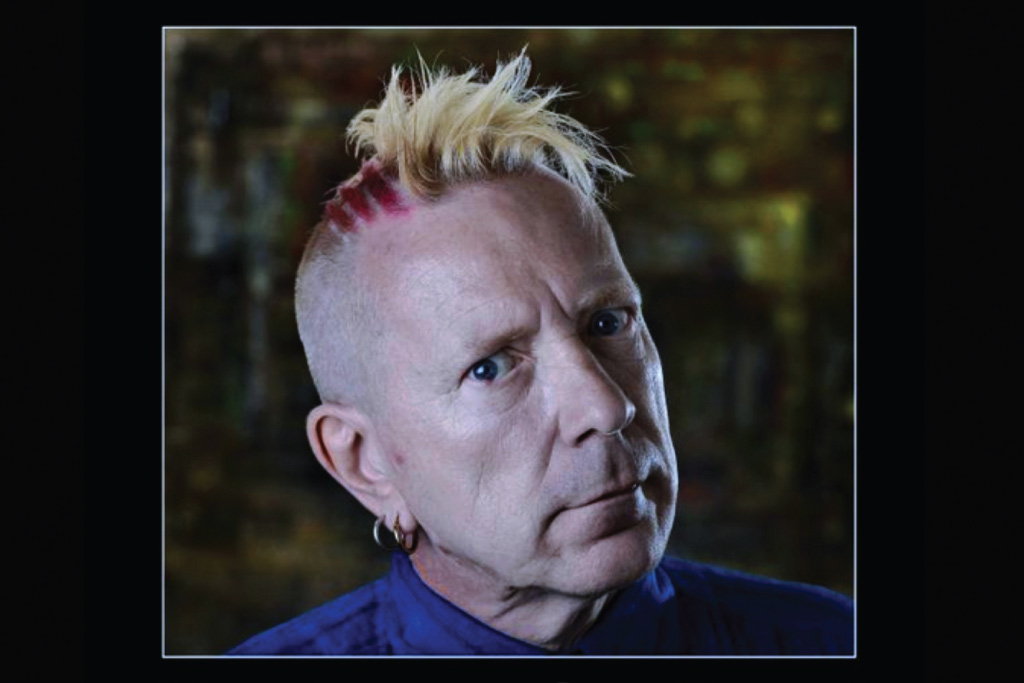

Capturing silliness while surfing a breaking wave of irony is evident in Bill’s many celebrity interactions. The “King of Comedy” Henny Youngman agrees to pose with a scepter and crown. The groundbreaking punk rocker Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols, now balding and middle-aged John Lydon, smiles sweetly with a new set of teeth.

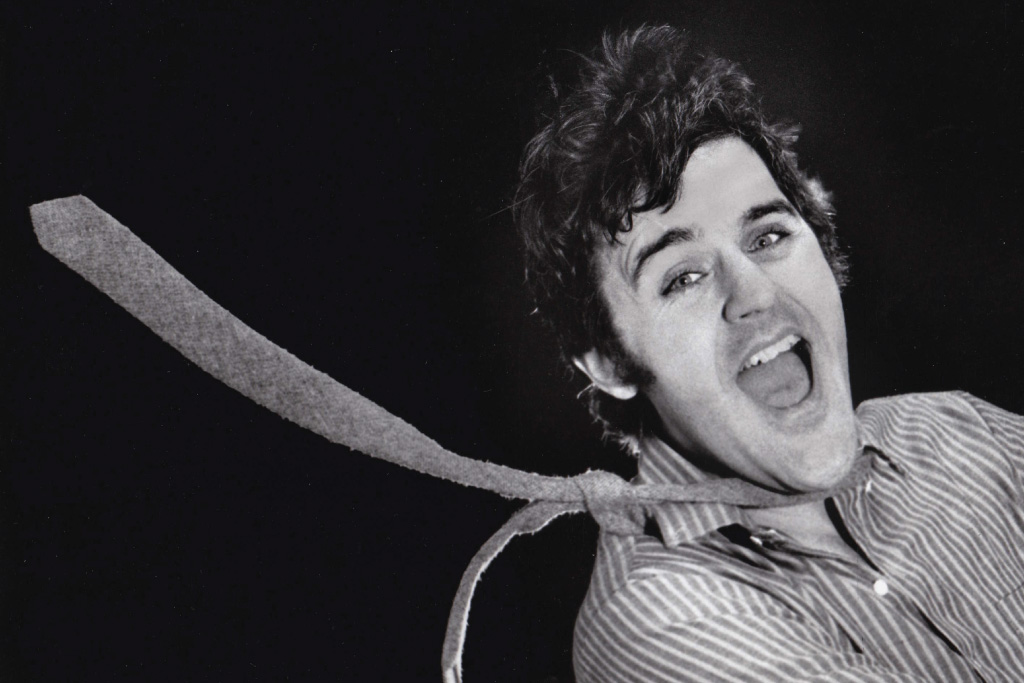

Hunter S. Thompson is shocked by beefalo as Bill gives him a ride into Grand Forks from the airport. His probing interview questions to the Violent Femmes frontman leads Gordon Gano to famously quote his own lyrics: “I hope you know this will go down on your permanent record.” Jay Leno pulls Bill’s tie off just to keep up with the goofy.

Becoming friends with the humor columnist Dave Barry at the Olympics, he feeds him wacky story angles (see: “synthetic wolf urine”) and the two go curling. He strums (with permission) B.B. King’s famous guitar Lucile, eats hot dogs with Davy Jones of the Monkees in a school gym, and Lydon feeds him chocolate chip cookies.

“The picture is good, but the story is better,” Bill says. “That’s happened several times in my life. That’s my whole job.”

John Lydon, interviewed and photographed by Bill for an online profile in the Orange County Register.

Dave Barry went curling with Bill for a story during the Nagano Olympics, but couldn’t handle the stone.

The Violent Femmes chill out in a beer cooler in East Grand Forks for a Dakota Student portrait in 1984.

A young Jay Leno dons Bill’s tie for a portrait session before his show at the UND Student Union.

Life isn’t all cookies and curling, and Bill wades into the biggest story in Grand Forks history: The flood of 1997. The Red River overtops. The city is evacuated. And then downtown catches fire.

Bill puts on chest waders and strides blocks through 38-degree water, snapping as frustrated firefighters surge silently through the turbid flow toward the flames and smoke. The result will be a front-page photo of the heartbreaking disaster.

At the Air Force Base hangar where evacuees perch on cots, the newspapers are quickly passed out, but no one speaks. “Then, whimpering and sniffles,” he says. “It was the first time they saw what happened to their town.”

Bill wants to memorialize the story on video. He gets a grant from the Otto Bremer Trust to make the documentary “Come Hell and High Water.”

“Proceeds went to a particular FEMA trailer park for a laundry facility,” he recalls. For his efforts, Lutheran Social Services gives him their Good Guy Award. The film premieres at the Empire Arts Center in downtown Grand Forks.

“I just stood in the back of the theater and again, the quiet and the tears.”

Bill attributes his iconic photo of the Grand Forks flood (and fire) to knowing the city well due to having lived there for five years. “I knew how to get around all the road blocks.”

I’m on a long call with Bill, talking about language. His condition is advancing, but it’s early 2020 and he’s still able to handle most of life’s needs.

The work has ended, which might crush another man, but Bill turns his attention to a bucket list. Stories to tell. Deadline looming.

An old UND friend gave him a jersey from the Spokane Indians baseball team, who worked with the Spokane Tribe of Indians on a logo that incorporated the team’s name in their tribal language, Salish. He thinks, why can’t we do that for UND? The former Communications major taps into a story: tribal languages are endangered. He decides that t-shirts combining a new image with the old language13 will not only raise awareness but raise funds to teach the language.

Friends and donors don the green shirts with an icon of Chief Thunderhawk at the center, surrounded by Lakota words. The Four Winds school basketball team on the Spirit Lake (N.D.) Nation gets a load of shirts too, which pleases Bill immensely.

He jokes of completing his list “before my bucket is kicked over,” and tackles other stories, such as getting VA benefits for Marines who were stationed at the same camp as his father, Ray, and who may have contracted the same crushing disease from chemicals used there. “The reason I got sick was to tell my dad’s story” and hopefully help other Marines, he says. In dreams, Ray smiles at him.

In the same vein, he lays bare his own plight for stories on ALS, speaking of the ravages of a progressive disease for which there is scant treatment and no cure.

Bill’s bucket list drove him to create a t-shirt with Native American imagery and lettering to raise money for Sioux language learning.

Taking pictures is illuminating the important things and letting the rest go dark.

We’re sitting in my car in a public park, watching people and discussing light. The essence of photography must be understood to compose a photo and capture that unique perspective. “My sophomore year at UND, I was shooting a picture of a dog catching a frisbee,” he says.

“I wasn’t thinking about the dog, I was thinking about developing the print. This was my aha moment! Shoot it so that the background is out of focus. I thought about that. Photography is about making three dimensions into two.”

He discovers he is “looking at the world and constantly taking pictures and cropping it.”

He realizes that the focus of his new craft — what makes photography even possible — is also the motto of his alma mater. “Lux et lex,” he says. “Light and law.”

“The law by which I live is light. Taking pictures is illuminating the important things and letting the rest go dark.”

Bill Thorness, ’82, is a Seattle-based writer and editor. He is the author of five books. His most recent, “Cycling the Pacific Coast,” is a guidebook for the most popular adventure cycling route in the U.S. He has also written “Biking Puget Sound,” now in its 2nd edition, two books about growing food – “Cool Season Gardener” and “Edible Heirlooms” (both illustrated by his wife, Susie Thorness, pictured at left at a St. Paul Saints game in June 2021) – and a profile of an auto industry executive, “POWER.” He has been an editor and writer in Seattle since the mid-1980s and currently freelances for regional media, including The Seattle Times. He is currently at work on a memoir about his father’s World War II service as one of the country’s first commandos. See more of his work and get in touch at www.billthorness.com.

Bill and Suzy Thorness and Bill Alkofer visited his “happy place” at a Saint Paul Saints game in June 2021.